- Home

- Garriga, Michael

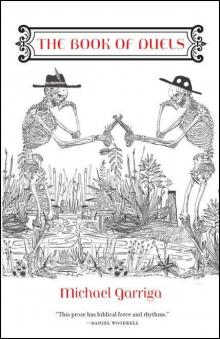

The Book of Duels Page 11

The Book of Duels Read online

Page 11

I turn and squeeze the stiff trigger—I know I am right in this course and God will prove me true with the aim of my bullet: hot sulfur smell, thick smoke in sunlight, and a snarl of flame like the hell we’re both bound for.

Etiene Thigpen, 46,

Veteran, US Artillery Division

He come home a fool-headed war hero to judge and insult me—we walked down to the lower field of fresh-turned earth—iron and onion and scat—where he accused me of stealing his cows which I had bought clear, got a cash ticket for proof, and now I’m sorry I ever prayed for his sorry-ass soul—sure I ran some hooch out to the blockade, but that don’t make me no damn traitor, just a trader with them boys in blue who gave me coffee—the same chic’ry then as what coats my tongue now—and more, I suffered the hardships of war, boiling seawater to get at the salt to keep my food, and done fought my war too—took a bullet in Mexico with Robert E. Lee and now my sweat-clammy palms wrap ’round this pistol butt, smell horse lather and oil on this iron piece, see them mildewed Spanish moss tendrils come ribboning off oaks slashed by sunbeams—accuse me of stealing and lying to boot, I refute his claim same as I did old Thibideaux’s back in ’53, may God rest his soul in smoke and flame eternal, Fire.

I turn and my hand blooms a white cloud of smoke as though I’m holding a fistful of baby’s breath: good gracious, boys, I’m hit and done; please say sweet things of me to Mary.

Mrs. Etiene Thigpen

(née Mary Annette Cuevas), 18, Watching Her Husband Duel

From where I crouch behind the pleached crosshatching of azalea branches, I see the two men standing back to back like stuck twins and wonder how they can be that close and not kill each other now—Etiene’s face flushed, his shoes, as always, thick with mud, and that preening blowhard, Philip, just as calm as Sunday afternoon, his clothes pressed and his boots polished and shined, prepared for death or murder one, yet it’s my hands that rattle these petals from the branches—beyond them the gulf catches the sunlight in little spinning coins, like the bright dimples in the cheeks of the Kaintock man who touched my wrist at the Saint Stanislaus social and who, in that moment, bade me run away with him to New Orleans—to stroll along the banquettes arm in arm under the ironworked balconies and to eat almond truffles or pralines brought ’round by Creole women wearing bright-colored tignons and hoop earrings that brush their bare shoulders like I wish I could wear mine—we’d attend the Conde Street balls, dancing and sweating under the flambeaux, where we’d glide through the measures of the contredanse or sip wine in the American cabarets until I’d retire to his arms and bed and he could take my ankles and toes in his mouth and I’d take him in mine and he’d not smell like cattle and night soil—I yearn to leave this backwood outhouse, these backward outhouse men, whose petty wars and self-puffery leave me hungry as the war ever did, when I had to parch corn to make coffee till my guts were pulled like the dead girl from my womb, whom I buried in secret while Etiene was off making whiskey or God knows what, to walk away as these men here have walked away, one from the other, but without sense enough between them to know it better to continue to walk and never to turn around as they have turned now—Fire.

A twin roaring, two great clouds of smoke, and a scream—I have prayed for this bittersweet moment—the taking of Etiene away from me—in my dreams I am not his little Mary Annette, hiding behind a bush, heart pounding so hard it makes my hands shake, but rather, I am the bullet squeezed from the burning steady barrel, freed.

Check, Mate: Johnson v. Rasputin

Nine Months after Johnson Was Sentenced to Prison for Breaking the 1910 Mann Act for a Crime He Allegedly Committed in 1909, Staying in a Royal Apartment, St. Petersburg, Russia,

March 3, 1914

Arthur John (Jack) Johnson, 35,

World Heavyweight Boxing Champion & Fugitive from “American Justice”

Pop put his belt to my back regular as the mindless and violent Galveston weather that spun his birds about in the sun and in the rain, and he would come again, a hurricane of a man, to hit me in the head with a skillet so’s I couldn’t run a comb through my hair for a week, or he’d swing his jump rope that whipped the wind just as it cracked against my skin, random as The Numbers, till that summer morn when I brought Mama’s red clay pitcher filled with water to the rooftop and there I set it on the stoop and removed one by one his trained pigeons from their coop and dunked them, beak-down, till their wings quit batting my forearms and their last living breath bubbled up and popped into thin air and was gone forever and then I set them out on a sideboard like in these pheasant still-life paintings hung against the velvet walls in this well-appointed room, just so I’d know the exact minute of my next beating—and it was my last one, too—as soon as I could stand again I left home and fought my way through the world and beat black men in makeshift rings or barbershops, but the first time I fought a white man, the cops threw us both in the clink with nothing to do but spar, two pugilists training for ninety straight no-women days, and he taught me to give it as well as to take and when I got out I swore I’d never spend another dime of my time in a place like that and I got out and put the whipping on blacks and whites alike, though truthfully, they were all just Pop to me.

Rasputin takes my queen so I, according to the rules we’ve invented, take another shot of potato vodka—twelve so far this game, our second one of the night—I stand to hit the head and go all wobbly, spin, and kick the board over, and the game is undone, pieces clink and shoot across the marble floor and I too hit the floor, cool and hard, and laugh, realizing for the first time in a decade or more, I have been knocked slap out.

Gregori Rasputin, 42,

Mystic Religious Leader & Advisor to the Romanovs

Here is God’s own hand at beauty, this mystical black man in fur coat and Buddha cheek, full of grace and fury and quick of wit and smile, but he cannot drink to save his life let alone his race or country, and there on the chaise longue reclines his whore-wife, who takes each shot like the Lord’s own body, and my Ekaterina strokes her hair and they purr together there and it remains unspoken between us men that the winner shall take all—this fighter, so used to having his way with every man he battles and every woman he woos, which is just another kind of battle, has left his lady open and I slide my bishop, cocked at an angle, right up her side and pull her to my lip of the board and I pour his shot rim-high and he holds it like a prayer bead, steady as winter hail, and throws it down and blows out his spirit and shakes his head and topples—his deep eyes roll back in his head like those of my epileptic sister Maria as she floundered in the Tura River below our Siberian home, not a bird above nor a fish below but snow and snow and cold cold snow—when they pulled her out her lips were the Prussian blue of cyanide—like those of my brother Dmitri, who with me fell into that same river and only I escaped to live and thrive—now in the Russian winter the pale air that twists from my lips is but their spinning bodies come to invade me no matter how I’ve tried to snuff them out.

I have always lived by this one creed: the greater the sin, the greater the redemption. It’s why I explained the pointlessness of flagellation to the Khlysty—if you are to deny the body, brother, why excite the senses with pain when there is so much pleasure to be had—now beside his sleeping, snoring body I will have my way with his whore-wife and as I twist the long strands of my chin whiskers and pull them taut, the Lord begins to excite and shake my crystal bones, move through me, and make my tongue the trumpet of His good grace with which to sing a gospel into the great chasm of these very Mothers of God.

Lucille Cameron, 21,

Prostitute, Secretary, & Wife to Jack Johnson

After that bitch lied on the stand, Jack skipped bail and we fled to a Mexican town where we could hear the church bells tolling all the way down to the beach where Jack and I, hand in hand, followed the mule tracks in the dry sand, the wind erasing them one grain at a time. We passed fishermen in wooden dinghies, which bobbed in the water like coffins; passed ki

ds who flew kites made of yesterday’s newspapers; turned off at Calle Vida and entered the town’s only cemetery, where we joined the old women who wore pressed and austere gowns, white with embroidered roses and tangles of thorny stems. They swept dirt and salt off their loved ones’ crypts and put fresh-cut flowers and candles on top of brightly painted tombs—pinks and pale oranges, light blues and greens—like muted versions of the hump houses in our Paris on the Prairie. I pulled away and walked back among the poorest graves, some nothing more than ash in a mason jar or a lone crucifix stabbed into the earth. And then this one: a small pair of faded blue pants and a red and blue striped shirt, both folded sharp as surgical tools, held in place against the blowing wind by an ash-filled plastic bag, and like a lambskin condom, it had burst where a bone that didn’t quite burn had pushed through. I put my fingertip to it, pushed it back as gentle as you please, and brushed away the leaves and said a prayer to Mary for this dead child and for mine too, who’d be about size enough now to wear these clothes.

Now sitting on this velour chair beneath crystal chandeliers that hang twenty feet above, I tamp the tears down, because I know there’s no going back to Mexico, nor to the United States, nor to a time before that law was passed, before they needed a Great White Hope and found it only in the form of Uncle Sam; back before the operation or before my innocence was stolen by Uncle Ray’s wandering hands—there’s no back at all and there’s certainly no tomorrow—there is only the giving in to the moment—Ekaterina’s hand on my thigh, her lips and breath on my neck, the moan caught in my throat, and this bright-eyed mystic standing before me, worshipful and tugging his beard. My man is the king—he has scraped through this life by way of nimble violence, though he appreciates delicate things—my thin wrists, the tsar’s Fabergé eggs—the sheen of a simple pigeon feather can bring him to tears—but this night is not his night: it will see no rise from him at all.

Me and the Devil Blues: Johnson v. Trussle

In a Cutting-Heads Contest near Itta Bena, Mississippi,

August 13, 1938

Robert Johnson, 27,

Author of Twenty-Nine Published Songs

Now I’m back in the Delta having fun and folly with the old fool, Charlie—sure I ran his name through some mud but just to bend his bones a bit—he got raw about it, pointed that fret-pressin’ knife at me, a simple threat from a simple gimp, and spoke up strong and stout and called me out to run guitars, ring notes from their necks, and I laughed and did a double take, couldn’t hardly believe my ears let alone my eyes ’cause they been bad since the day I’s born—reckon why I couldn’t recognize that white man for what he was, standing there at the crossroads where the low moon made a shade of him, like some beast in black clothes—he got me to hit the road, head out west to San Antone, where I stood in a studio facing peeling wallpaper and singing so soft they made me record each tune twice—I put my soul in them songs and he sold them by the thousands till they turned into tiny coffins holding dead tracks—when I play some roadhouse show people always beg I do exact as on that wax, you know, like I’s a jukebox built just for they pleasing, but to me that’s just a prison, and I am dead set against repeating myself like that damn clock ticking on the grade school wall above the picture of a lynched god, white as white cotton ever got, where I spent my days studyin’ how to jump a freight, didn’t wait to get put-behind no mule, hoeing up a row just to plod on back, so I quit that school and I quit this land and hobo’d a train north to Chicago, where I slept in cemeteries and sat on tombstones playing long enough that my fingers grew calluses so leather-thick I could grab a coal so quick out the fire and light my cig before I’d even begin to feel its warmth—still I can’t shake the eerie notion that my life’s passing before my ears and eyes—but if I’m hell bound, Mama, I’m ready to go; let the devil’s hounds howl for me through the night.

So play your best, Chuck, then step aside, ’cause I’m gonna cut you so swift and deep, you’ll spend the rest of your crippled life jaw-jacking ’bout how in this hell-hot weather you had your head severed by the damnedest bluesman ever.

Charlie “Trickle Creek” Trussle, 67,

Paraplegic & Unrecorded Slide Guitarist (Dedicated to Cedell Davis)

Say he done sold his soul to the devil but what could a whelp like this boy h’yer ever know about the real hell I been through, though I know good and goddamn well I ain’t got a snowball’s chance to beat him—his fingers nimble as spiders on a web, perfect as a pocket watch tick—still, what I’m supposed to do, take raw guff off this bragging rogue, let him disrespect me, call me Cripple Creek, as if having polio and being wheelchair-bound makes me less a man than him? Ain’t I throbbing with the same desire as any other body? But boy if my hands could bloom, flower like a fetus in womb, I’d make the tunes I hear in my head and shame this cur, smiling in pinstripes and plucking away. Instead, I scraped out bar chords and bullied short runs with this butter knife I stole from St. Anne’s Orphanage. And when he sings, Hello, Satan, I believe it’s time to go, I look down at the devil’s own doing: my claws; my fists curled tight into palsied balls, tight as when I’d crawl drunk into Lila’s lap as we lay in my cot out back of Manning’s Auto Repair, way back before she left on that Greyhound searching for someone to fill her with that baby she wanted; these same busted hands that could never hold still her steady rolling self, never mind the children we could not make.

In a flash I bust through my impotent rage and ram this blade through Bob’s thick skull, but then I’m sober and awake again, sitting hangdog and silent, listening at him strum and pick and sing so goddamn beautiful it makes me want to cry.

Lonnie Newhouse, 57,

Witness, Owner of the Crossroads Saloon, & Cuckold

Hush up and listen at him, will ya: I don’t care where you bury my body, baby, once I’m good and gone. This fool don’t know half the truth he sings yet I’m more the fool for bringing my old lady ’round him in the first place—I should have reckoned that look in ole Bob’s eyes the same as I give to them ole country gals—big thighs and jelly rolls—give em my rock and stroll home to sweet Irene—bathe till I’m fresh from beer and smoke and pleasure and flop beside her in our bed, where once I heard her call his name as she slept, though it sounded like his voice—thin and eerie as ghost speak—as if some wanting haint from another world was tasting on her tongue the name of its lover—at first I was spooked but then I grew howling mad as when Lou’s ole blue tick got in my coop and ate the day’s eggs, crushed them and licked they runny middle, which got me hot, sure as shit, but when I stepped into the light of day and seen the dead hens too, one after another littered on the yard, all twisted in bloody heaps, and knew he’d killed them just for fun—well, man, I went buck wild and straight off to the Dreyfus Druggerie and got me some strychnine and stuffed it into a chunk of raw meat and it was a pure de-light to watch that mangy dog suffer, moaning and whimpering three days into death—last night old Roustabout Tommy told me how this singing mutt here slicked my gal and tangled her hair good and I pictured them twinning and hanking on the bed where our baby was born and I began to howl and to plot—tonight I’m gonna do this boy in with a hot spiked drink of gin and then he too has got to go, I guarantee.

Custody Battle for Chelsea Tammy: Malgrove v. Bowling

At the Toys “R” Us, Aisle 6, in Minneapolis, Minnesota,

December 24, 1983 (for Jeanne Leiby)

Tyler Malgrove, 38,

Attorney & Divorced Father of a Six-Year-Old Daughter

I am a trial attorney. I make a damn respectable living through confrontation. I own a Saab turbo sedan, a closet full of Polo and Armani, and a Movado watch my wife gave me on our fifth anniversary. I bought a three-bedroom ranch and my Jennifer attends the finest prep school and my wife drives the Volvo 240 that I paid for in cash and lost along with the house when she divorced me last year. She was a cheerleader, my wife, at the University of Georgia, and her legs are long and golden. She is great at parties, her platinum

feathered hair tousles when she laughs, and when she laughs, you are the only man in the world. And whom does she laugh for now? When she leaves a conversation, she’ll touch your wrist with her long bronze fingers and you go deaf for the next four minutes. And because our daughter’s play pals all have this doll, she must have one too. The hell with the forty dollars; I want her to be supernormal and I want my old life back. So I slipped inside my Lucchese boots and drove to five different stores before I arrived here to find the last doll left on the bottom shelf and so I reach for little—what’s her name?—Chelsea Tammy, with her red yarn hair and dimples, when some guy decked out like Rambo in fatigues and dog tags and lank hair tries to take her from me. I say, Sir, I believe you’d be more fit for Raggedy Andy. My kid may not have her father now but she’ll damn sure have whatever else she wants—when he reaches for my tie, I slap his hand away.

Buddy boy, I did not grow up picking cotton in northern Alabama, did not join the National Guard to pay my way through undergrad and law school at UGA, did not woo a woman as beautiful as all the gold in Fort Knox, did not join the bar to gain a foothold in society and earn the respect of men better than your vagrant self will ever be, and certainly did not suffer through a very messy and very public divorce, which left me bankrupt of money and wife and child, just to lose what my baby girl wants now. Not to you. Not to anyone. I say, Unhand me, sir, and then, as his grip tightens around my throat, I squeal, Or I’ll sue! I’ll sue!

The Book of Duels

The Book of Duels