- Home

- Garriga, Michael

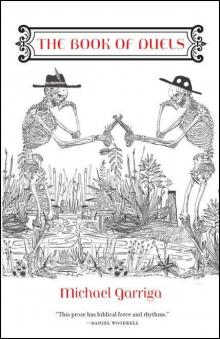

The Book of Duels Page 7

The Book of Duels Read online

Page 7

My trigger finger taps the pistol butt as calm as turning a trump—there are so many ways to die, I reckon a man oughta consider hisself lucky, notorious at the least, to celebrate these victories over Death—specially, when it gets told and retold, if he’d shot twenty-four border ruffians with only six bullets, killed the strongest gotdang Indian chief with but his bare hands, or had the hair on his ears singed off when ever durn two-bit Reb shot his way at’wonce—they all wanted me affrighted but really what is there to fear? Nothing, ’cept being forgotten and I don’t reckon that’s gonna happen to me neither: so buck up, Tutt—you ain’t got to grieve too deep ’cause after I kill you here and now, you’ll be infamous too, and I’ll be hanged if you won’t have been the fastest gun in all the West, until you met me.

Davis Tutt Jr. 29,

Confederate Veteran, Perpetual Sidekick, & Gambler

I come out the livery stable to find him cool as Ozark dew and leanin caddywamp on a pillar of The Lyon House and I stand tall as can do and open my coat to show his watch hangin from my fob chain for all who care to see—his bright blue eyes turn that steel gray they get when his blood is up—he is a Yankee, Bill is, and I kilt a dozen or more of his kind in the war but all of em taken together ain’t his equal—he and I rode the ranges this spring and drank the taps dry and I brung him out to my kinfolk farm where he sweet-talked Sissy and sneaked off with her to canter rear of the barn and he went off and did her dirt—before then I’d have torn the eyeteeth out a wolf’s mouth just to get corned with him again—I swear I wisht I ain’t knowed what all he done, so I ain’t have to make this choice here—family or friend, honor or fear—’cause I’ve seen him shoot and he is true with a bullet and he got the good nerve cept when it comes to cards—that tick in his jaw means he ain’t got the trick nor the bluff he shows and so I aimed to beat him out his bankroll but snatched his watch instead, just to break his heart a bit, and now he wants this spectacle show so he hollers across the square and I, I tug my piece from the holster slung low across my hip and I am in the dad-blamed war again—brother versus brother—I see my shot bury in the dirt, spittin up a tornado gainst his moccasins, his thick thighs in leather leggins, his narrow waist, his broad buckskin-covered chest, and on up to where the white smoke hides his hand and hair and fine, fine face:

I am blown clean through and goddamn it hurts—the whole blasted town of looky-loos stares from behind the water troughs and billiard hall windows and saloon doors—Send for the surgeon, you sonsabitches, don’t just stand there stock-still and watch me die—my scalp prickles and I fall on my haunches, sittin in some mud—who knew I had all this life inside me just waitin to come on out?—my head swoons silly and I close my eyes and feel Bill’s hand steady my shoulder and I realize I have often wanted his hand on me and I look up but he is not there and I fall sideways and I just keep falling and falling and

Dr. Aleister Greggs, 63,

Former Surgeon, Present Drug Addict, & Future Dime Novel Author

I exhale the smoke and a certain peaceful silence blows over me and I roll to my other side to look through the dingy lace curtains of Lu Yang’s upstairs window expecting the clouds that attend high noon, but instead the evening sun shimmers like a crimson pool on the tin roof of The Lyon, with its venetian blinds and fancy chipped-ice drinks, and beneath stands Hickok, the biggest toad in this whole mud puddle, his fingers all a-wiggle above the hog leg jammed in his red silk sash—this morning he and young Mr. Davis called on me as if I were the swamper sent to sweep the sawdust and slop the spittoons but I storied them on the preacher who I saw shoot a newspaper man back in ’59, who bled to death jabbering on my parlor room rug—shot him in a duel right in front of the dead man’s boy who later, I heard, gave that clergyman the short end of the horn—I gave both boys to understand that I’d not be put upon to clean any more wounds, nor ease the pain in any way of men who shoot one another, and I assumed that had settled the score and so we’d have no bloodshed today—across the square, where flies have gathered on every pile plopped in the dirt, comes ornery Davis walking down Business Street, where wagons and horses and mules stand before the mercantile and blacksmith shops, and he’s all squinty-eyed against the sun, his long coat blowing in the wind, and I conjure in this yellow silence a hawk’s shadow inking the earth between the two men and then the bird screes—I can’t get shed of all the death cries of Quantrill’s crazed bandits back in the war—boys, just boys, slathered in their own gore and I’d ply them with opium powders till I took a mind to dope myself and when the war finally stopped I prayed for a certain peace, but those ghosts speak shadows that never cease nor do they ever sleep nor disappear.

Their pistols jump together as in a dance and the smoke rises and Davis spills a mess of blood and collapses into the mud of his own making and hollers for me to help and Hickok turns back inside the saloon for a belt of rye, I presume, and I ease down the water-stained shade on the world and roll back over and take the pipe to my mouth for one more puff of God’s own medicine, and as though it were the lost souls of every murdered man I’ve ever met, I hold that smoke in my blood and brain and lungs until it burns and has to come out.

The Black Knight of the South (A Gothic Romance): Moran v. McCarthy Jr.

In the Fourth and Final Duel of the Day on Bloody Island in the Middle of the Mississippi River, Near St. Louis, Missouri,

March 23, 1874

Cadet Moran, 14,

Youngest of the Moran Clan

My brain’s a dang swarm of bees and that judge just keeps on a-counting and so I count too: my three dead brothers laid out on cooling boards, the color yet in their cheeks; my first duel ever and his fourth today; one bullet in this one pistol in this one life; and six vultures lazy-eighting on the wind, which is God’s breath come to cool my skin now as I lick my wrist, thin and clammy. My tongue is pruned. My mouth, cotton. My legs are logs on fire. And the river and the smell it carries from a thousand miles north, is pulled past here roaring like a dad-durn tornado and my numbers go all jumbled and I want to dive in the water and be done with this mess but if I ever wish to look my kin dead in the eye again I must be here to defend Sister’s honor and avenge my brothers’ deaths—though I’ve never worked a hard day in my life, instead of these paces I’d rather be walking behind a mule like the tenant farmers who plow our land, or better, digging in the dirt for worms to go cane-pole fishing in Simmons Stream or swimming out there with Jeanette or chasing her through those fresh-turned fields, pulling her ponytail instead of the trigger to this gun that weighs nigh as much as me, but I am here, fingering this cold iron curve, as the judge calls twenty and I stop and spin slow as the seasons change and I see my man and I can’t shake the blasts fired earlier today nor the way my brothers bellowed when their blood burst from their bodies, freckling the sand—I clamp my eyes tight as pickling jar lids and the judge hollers, 1, 2, 3, Vale—

I hear the report clear as church bells but I swear I ain’t even squeeze the trigger. I swear. Yet there he is somehow splayed on top of Sister and she’s a-kissing his face and I fall to my knees hard in the sand and pray that my brothers now may all rest in peace, though I know I never will again.

Ms. Mintoria Moran, 28,

Only Daughter of the Moran Clan

When our skiff struck the shore, I snatched the derringer set beside Doc Reynolds and hopped out the boat, water licking my ankles, and ran to Mr. McCarthy—my Alex, my Lex—the wind whispering against my thighs—oh, may he ravage the world but not my Cadet!—I cannot bring myself to consider him on a bier beside his brothers, not my Cadet, brother and nephew and son, born so small and squeaking in that Natchez nunnery where Father sent me to swell and whom I carried in, and fed with, my own body—certainly not now when it is spring and the first crocus fingers have pushed through the wild moist earth calling for human fingers to push back—to plant seeds, not bodies—these thoughts go hissing like kettle steam whistling through my mind mingling with the odor of Lex’s skin—that

deep scent of sandalwood makes me a weak-boned six-year-old in Father’s lap, wagon-bound home from market, sacks of vegetables stacked behind us—I was only going to fire a warning so he might lay down his arms and take me up in his as he did this morn when I poured his tea in Mother’s fine wedding china—that smell came over me and my bosom swelled and I swooned and spilled his drink on the red parlor rug and took his face in my hands and kissed him hard on his lips and pressed him to me and he pressed me back, kissing me—John walked in and slapped me and slapped Lex too—John, the same brother who came to my bed and put his hand across my mouth and done those things he did and said it was all my own silly fault—if Lex had killed only John, or only all three of them boys, I’d still have run away with him as far as San Francisco—instead he accepted Cadet’s challenge with all the passion of a man asked to pare an apple—so I come to this island for the first time to hear the judge call Vale—

I run yet faster and Lex stares at me and stands still as his walking stick, his long curled locks black against his bone-pale skin, his silk-lined cape whipping in the wind, holding that position like a half crucifix, and of a sudden, he folds his arm up under his chin and the smoke rises ’round his jaw hasps even before I hear the shot—his scalp lifts as if he were merely tipping his top hat to me and he steps back and bows and lists and falls—I am breathless but there to catch him in my arms, to rest him in my lap, to put my lips to his moist hair, sticky with the same garnet that splays across my white skirts, and the sandalwood smell now couples with an iron taint and he jabbers through shaky lips about matricide and marriage and one night in a castle with a son who should have been killed.

Alexander “Lex” McCarthy Jr. 28,

Winner of Nineteen Previous Contests

I stand here again on this towhead spit of land, Father’s etch-handled Manton warm in my hand, my thumb web tattooed black from all the powder I’ve spent today—I try to read my future in the markings but all I see are streaks of dark chaos, and now this last one, the baby, has come like his brothers to be brought low by the best shot artist ever known and it is a shame: during my three weeks here I’ve admired this lad, rambunctious and guileless as a baby raccoon, the kind of kid I might have been if Father hadn’t proven himself coward and damned me to this life of constant killing—though that’s not the truth—I was born a killer, carried my mother off on my very first day of life, and I came to this estate to take it for my own, to build a castle overlooking the river—then I met Mintoria—I had to take her too—Cadet could have called me Father, instead he called for my blood, even though I put my last ball in his brother’s heart and the one before right through a vest buttonhole, and for the first one, John, I won’t even ask God’s mercy—he invited me here, one more speculator to rob, and, as often happens with money and women, our business ended with a bullet in his eye. I saw him look at Mintoria, covetous as Amnon, just as I see her now, dainty feet churning the loam, her skirts held in one fist—and what’s this, a small sidearm in the other—running straight at me. I draw a line in the sand with the heel of my boot, take careful aim at her final brother, his eyes slammed shut, and I can go to my grave certain he too would have fallen on this island—Father put his pistol skyward and sent me surely to hell—how many have I killed since then, their faces coming, twisted, to me each night—I can never delope nor allow Mintoria to enter this horror of honor and death, so I decide on a thing I’ve always feared, and the judge hollers, Vale—

Knowing there is no shot as worthy as my own, I press the barrel under my chin and squeeze out a prayer—the wind rips through my skull and my bullet carries me into a million falling stars and I’m stretched so far I can’t even see my own boots—Mintoria is beside me, pray—I try to explain but I can’t ’cause the time has come for me to join my father, Heaven still at a damned remove.

Catfight in a Cathouse: Carol v. LaRouche

Two Whores Brawling in a Storyville Brothel during the Last Month of Legalized Prostitution, New Orleans, Louisiana,

April 13, 1917

Cora Carol, 19,

Prostitute in French Emma’s Circus

Pap sets his lens just so and measures the light and lights the flambeau and measures again before he duck-waddles his dicty self back to the camera and whines in his high nasal voice, Stay still now, Sistuh—for the five dollars he offers I’d stretch his bellows let alone sit here naked on a clean couch—I shake, laughing, and he says, Corpse-still now, les ya ruin da print, and I wish for a flash I’d been a stillborn and not a trick baby delivered in this Tenderloin District of men, though they mean very little to me save the money they bring, like when I walked in on Ma as she dissolved the purple salts in a washrag to clean her john who stood there naked and limp, potbellied and hairy, gazing at me in my white party dress that made me look even younger than my ten years allowed, and he said, Why don’t you give your mama a hand? and I shrugged and took up the cloth with no more thought than when each Monday I’d take the gals’ bedsheets out—all yellowed with sweat and spilled seed and Rolly Rye—to scrub and tug them clean, which I did to his prick and it swoll in my palm, straining against its own fleshy self, and so I squeezed it more till its top pushed out like some purple-headed turtle and the man moaned and tangled his fingers in my locks and tugged my head back till I saw his eyes closed and Ma guffawed, Well hell, honey, go on ahead, and I froze till she put her warm fingers over mine and we tugged together only twice more before he spit his load on my forearm, which I yanked back as if it was snakebit, and Ma laughed hard—hair and boobies bouncing, head thrown so far back I could count her cavities—and his grip loosened in my hair and my scalp tingled good and he slumped down in the chair, fuddled his drawers midway up, and took from his pocket a five-dollar tip and Ma come up with a clean rag and said, Oh my, and took me next day to Krauss Department Store where I bought white gloves and opera-length stockings like any other whore.

Now Vivian crosses the floor—the odor of rain and roses, all legs and eyes and a sneer spread across her fine face—under her breath she says, Bulldagger, and I’ve never felt shame for being a whore any more than for being human, but just now I feel as if she’s caught me diddling myself to a sticky picture of her split lips, my nipples stiffen and as she passes between me and the lens, touching her chippie ribbon, I leap from the couch and snatch that bitch by her long hair and I bang her against the wall.

Vivian LaRouche, 15,

The Flying Virgin, Featured Attraction in French Emma’s Circus

I walked in the parlor and saw Bellocq acting prissy as a queen in heat, fluffing a pillow and worrying the knot in his soft pink scarf, set to make a likeness of ugly ass Cora, the heavy degenerate—God only knows why, when not one man I’ve known has screwed her in the light of day nor lamp—when he should be making my picture again, because I’m the one here the men come to see, when in the theater I hang from my silk ropes, swinging bare-breasted and bewinged above braying Emma, while she is mounted by her rutting Great Dane, my braids rising and falling against my pale back, my feet pointed far out as I can stretch them, admiring my own knees and thighs and thrush, and I know the men have paid dearly to watch me and touch themselves—I can’t read a lick except that look in a man’s eyes, but Daddy wouldn’t even glance my way when he dropped me here three years ago today—Emma putting that stack of money in his left hand, the tan line precise from the wedding ring he’d buried with Mother—I’m going to be a star on the big screen like Lillian Gish or Marguerite Clark, whose films I’ve snuck out of the District and into the Quarter to see, and though I know if I’m caught over there I’ll be arrested or beaten or raped, I will continue to cross busy Basin and Rampart Streets on down to the Louis Gala House where they show films for a nickel apiece, and as I sit in the dark watching their large eyes on screen, I say to myself, Vivian, that is going to be you someday soon, and Daddy, I swear, you will have to pay to see me again.

As I cross the wide-plank floors, I happen to pull the string of my

dress and it comes undone and my chest rises against the lace and pushes it apart and I stare first at Bellocq and then at his camera’s one big eye and my lips swell and sweat and begin to itch a bit—does he touch himself when he holds the portrait of my nakedness?—my head snaps back and I’m pinned on the wall with that dyke’s breath in my ear and I bite her forearm and twist her chin back and bury my thumb in her eye and we crash to the floor and she’s pounding my head into the wood and I wish I had my razor to undo her with, because though I am very small, I am not an easy row to hoe.

John Ernest Joseph “Pap” Bellocq, 43,

Photographer

Cora and Vivian tuggled and tussled and upset the lit flambeau though I caught it, screaming, Watch da flames, my voice high and shrill like the horror of a baby’s wail—Watch da flames, my parrain yelled—him, swatting mad with a blanket in both hands trying to put out the blaze that climbed up Sister’s crib; her, squalling as fire caught her flannel gown and hair; me, having begged for him to leave the lamp lit while I slept a bit longer and who in dream-terror of wild worms and rutting rats in my brain had kicked it over and burnt my baby sister damn to death—gone now my father and mother and my sweet big sister too, my only brother off in the ministry—I alone am left to stand against Death like Madame Josie, the grand demimondaine, whose portrait I made to hang on her crypt door beneath the statues of the little girl and the twin pillars of flame, and though I set her likeness a mere three years ago, the sun has bleached it back to a silver-slabbed mirror and now when you visit her memorial you stand agawk greeting your own gape-mouthed visage on the bronze door of her tomb, which reminds me of my own burial plot—I can see it from my bedroom window and there too I can hear the pistol fire from Marcet’s shooting gallery and see the government eviction posts on every building in the District and the paint peeling off Willie Piazza’s mansion in great white swaths long as funeral tunics—all this after I’ve returned from my pleasure at Anderson’s Annex where the boys belly to the hand-carved bar and snook schooner after schooner of beer under the one hundred electric bulbs blasting the dark back in a blaze of white light, but up in my room it is quiet and dim and I wash my face in the basin and remove my clothes and put on my nightshirt that smells clean from powder and climb into bed to sleep with the lamp lit beside me.

The Book of Duels

The Book of Duels