- Home

- Garriga, Michael

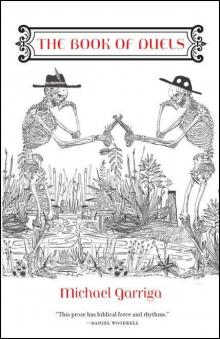

The Book of Duels Page 9

The Book of Duels Read online

Page 9

He calls me beautiful and I call him a liar and shift in this microfiber chair, the backs of my legs sweating even in the artificial cold of this office, because who is beneath this layer of powder and rouge, this four-layering eye shadow, this gloss and lipstick and lip liner, this bobbed blond hair and these earrings, I don’t know—peel back this mask and who is there—in that Motel 6 in Grand Rapids you promised me the Ms. Corn crown but all I really wanted was someone to see who I truly am and to tell me, though the only way I know how to ask it is by smiling broad, Vaseline smeared across my teeth.

William Sellers, 42,

Jeweler, Father, & Unfaithful Husband

Six Saturdays in a row, D’s dragged me here to listen to this so-called doctor talk about trust issues and acceptance and respect but I am not the one who closed the door on this marriage, clamped it tight as a chastity belt, and for all the money this doctor charges you’d think she’d offer me a scotch or at least an orange juice freshly squeezed between the knees of a sixteen-year-old Filipino girl and the doctor asks why am I smiling and I say, whimsical-like, She’s the most beautiful woman I’ve ever known, which is true, or at least was true, especially when we’d walk along the summertime banks of the Mississippi, her long legs drawing every man’s eye, and I was not middle-aged then and there was not the pressure of employee health insurance and a child and retirement and savings, just our hand-holding strolls—that was back before D let herself go, and suddenly she says, You’re such a liar, and my face flushes and before me I see Peggy through the small window of my office—she is standing at the counter showing earrings to a customer, Peggy’s narrow hips and long waist, and she looks back over her shoulder and I am caught, but she winks, blows a pink bubble with her gum, and smiles with the dark shade ringed around her ruby lips and I’m a fool sitting at my bench re-sizing some heifer’s wedding ring and now there is hail raining against Peggy’s metal window awnings, the sound ringing in our afterglow, the window unit in her double-wide hums, and her panties ring her ankle, one shoe still clings to that pale foot, the salt smell cologned about us—my own wedding ring in the glove box of my new Boxster—the ring around the tub where we made love all last winter and Henry the dachshund runs rings around the playpen and Tiny Toons is on the TV even though her kid passed away two years ago and she told me yesterday that I said I’d leave D but I don’t remember ever saying so, or even believing that, though I can see my marriage is dead as dead can lie, ring around the rosies dead, but I am not willing to lose little Louise or half my things, like my fine jewelry or my red convertible that wooed Peggy to me in the first place—pudging and balding, skin loose about my jaw—and D says, Damnit, I want out of this life, and I repeat her, You want me out of your life, and she says, No, I want out of this life, and I say, That’s what I said, and we start to argue again and yell and we both see the light of freedom yet neither of us is willing to let go of this darkness.

PART III: SATISFACTION

Delivered into His Hands: David v. Goliath

In the Valley of Elah,

1025 BC

David, 16,

Eighth Son of Jesse, Bethelemite Shepherd, Poet, & Musician

I was in the southern pasture among my lambs and fertile fields, chanting dirges to the dead, when an angel of the Lord, white and ethereal, came upon me and said, Behold, David, King of the Israelites, and I shivered and my heart was quickened and I said, I only want to sing songs to my living Lord, psalms of devotion, psalms of praise, but it said unto me that the Lord had chosen me even before I was born—there was indeed no choice to be had—I laid out my harp alongside my staff and took up my sling to the field of war—I do not fear for I have already smote a bear and also a lion—as if the angel could read my very mind, it said unto me, His holy aim was true even then and shall remain steadfast unto this day, young king, and He will protect thy flesh also from harm, and I went into the brook banked by cedar and by juniper and the water was cool about my feet and ankles like the cold compress Mother laid upon my forehead as I raged feverish and demented in bed, thinking surely this was death but it was not death—instead it was the first time the angel came before me and spoke and I could see the light of the Lord even as I shivered and raged and when the angel left my side, the burning left my flesh as well—now I run my fingers across the smooth stones of the brook bed and pluck them as if they were strings upon my harp and I hear a music that shakes my bones, and though I am little, my wrists and ankles are large, my feet and hands are large—I take up five rocks and deliver them from the brook bed, as I have delivered the lamb from the bear and also the lamb from the lion, and I put them each one by one into my pouch and my body is covered in sweat and I dip my head into the cool water and it plays over my hair and into my scalp and rolls down my neck and spine and I stand straight and say, Lord, show me the way.

Goliath, 39,

Twelfth Son of Abimelek, Half Giant, & Philistine Warrior of Gath

No man like me, no man like me, I overturn your temples, uproot your largest tree, I thump my breast covered in bronze and it resounds with a gong and the armies behind me answered after this, chanting, No man like you, no man like you—I pace before the very army of Israelites and I am bereft of arms, only my hands calloused from long hours of grappling these runts—Which man among you will yield himself to me, will have the sincere audacity to stand before and not wither like the dry vine, the grains of time slipped through the hour glass? They are sore afraid and dismayed and I am elated because my ribs still ache from the blows I took last time I saved my puny men from certain death—our gods of iron have left us in this waged war, hidden, not to be found—I cannot fight them all for I am but half giant, not the full-flung fury of my father and half brothers—alas, I am but ten feet tall, my uncut mansword a mere cubit by my hand’s measure—I am tired and I will not be able to save us again—I shout them down to scare them away, Let’s have him quick and be done so I may return to the fun of sleeping with your wives and eating your children, and then he comes:

A mere boy in a loincloth, comely and soft—his armored brethren deride him as did my own half brothers me—full giants, they used to jeer and kick at me as they held my wrists and made me slap of my own face and said, Why are you hitting yourself, Goliath? Why are you hitting yourself? And I’d cry and try to hit them back but they’d palm my forehead, their arms impossibly long, I could never reach them with my fists even as I’d swing and swing and swing—I called after the boy in this manner, saying, Come to me and I will give thy flesh unto the fowls of the air and to the beasts of the field, and in turn I hear him say, I come naked save for my Lord of Hosts who shall deliver thee unto my hands, and he begins winding his sling above his head, each time it passes it appears as some god’s winking eye, and then he grunts and lets it fly.

Ephram of Gath, 17,

Only Son of Mutawadd’i, Philistine Slave, & Shield Bearer

I have stood beside Goliath each of these last forty days, his armor bearer, his boy with spear and shield—I have no choice in this state, I have been made his indentured servant—true, I stole a sack of acma to feed my starving child and I was caught bread-handed and the priests punished me thus—we have thousands more men than they but our courage has flown and we do not march on their army, instead we parade this one hulking hector to shame them into submission and who can fault them their fear—then comes the boy, unarmed save a sling in his hand and a song on his lips, and he is ruddy and goodly to look upon and everyone goes so quiet, verily, you can hear his footfalls in the sand and he calls to Goliath with a wave of his hand and Goliath turns and I hand him his spear and I hand him his shield and his sword is sheathed and his shadow is long through the valley—the wind kicks sand into my eyes and the boy whips a stone that catches my man in the leg and shatters his knee, but before he hits the ground, the boy has rushed upon him and unsheathed Goliath’s sword and, in one poetic gesture, brought it down upon his neck and, in this endeavor, severed the giant’s hea

d and freed me as well and the clouds part and a great stalk of light strikes me full on and I fall prostrate and repent my many sins and this boy touches my spine with the tip of the sword and I right myself, speechless, as he hefts Goliath’s head by its hair and his army rushes forth on all sides like floodwaters bursting a river’s bed and my godless army flees, impotent and ashamed—I embrace this boy’s legs and kiss his feet for I have found my king and I have found my God.

Dueling Visions of David: Donatello v. Michelangelo v. da Vinci

Florence, Italy,

1440–1505

For the Lord seeth not as man seeth; for man looketh on the outward appearance, but the Lord looketh on the heart.

I Samuel 16:7

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi

(a.k.a. Donatello), 54, Creator of Bronze David, 1440

He need not be muscular nor strong as the classical nudes but in fact can be effeminate and small as Giovanni when he sweeps the shavings from the studio floor—his sandals and hat are comely as are his long curled locks and his jutting round belly, so like a woman fresh with child, and my David is a child too, a shepherd from the field—it is not his might and brawn that win the day but rather his courage and faith that God invested within him—even the meek can inherit the earth if God is but within them—I have made him proud over the vanquished villain but I shall not circumcise him no matter the Judaic law because Giovanni’s lovely member is still intact and often on display as he models for clay drafts in my drawing room, the light coming through the high windows as dust motes dance about us, and we are done for the day, the drawings have been made and the models completed—the room is clean although we are lousy with sweat and debris and I towel him off and he towels me off and we lie beside one another on the featherbed above the straw mattress, where I often go for inspiration, and we close about us the curtains, and though the Florentines have banned luxuria, I shall not be bound by their laws or their art and so I have created something new, something built upon no known paradigm, and the Medicis can refuse their patronage, rescind their money—they can take this bronze back and melt it down, bust it, hide it away forever, but I will know what I have created here and I will be my own man despite the thousands they’ve persecuted for love—the smoke from my tinderbox envelops us as we ignite a fine fire and recline, warm and safe in my studio, and as far as I’m concerned, the Medicis are the giant, the powerful, the obese, and I am the mere naked boy who has conquered it, put my foot on its decapitated head, and yawned, even as its beard tendrils tickle my leg and beg my attention.

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni

(a.k.a. Michelangelo), 29, Creator of Marble David, 1504

As a child, I hiked among the snow-dappled ash and maple and beech of the Alps and ran my hands over the contours of rock and thought, Rain is the greatest artist, but now I see that idea as but the folly of youth, my enormous ignorance alone saved me from blasphemy—rain is but a tool wielded by the Great Practitioner, just as I use mallet and toothed chisel—those behemoth rock formations unknown centuries in the making, chipped away one wet drop at a time—oh, the patience of the Creator!—the images they hold still not apparent to us mortals—and that is the hell in dying—all that unfinished work I will never live long enough to realize—so when I saw my David trapped within the Meseglia stone, I knew it was my God-given duty to carve and coax him free, to birth and deliver him, and by pitching large portions of unwanted stone, I began to take away everything that was not of his form until this final figure remained, coolly posing in contrapposto just before he enters battle as I did with my mentor, old Ghirlandaio, who refused my wages but whom I have conquered and surely surpassed—my David lives forever on the hinge, a coil of potential movement, the moment before his immortality—here is a man who has made a conscious choice and will soon spring into conscious action like I with hammer raised over rasps and rifflers, abrading the stone into folds, and with a sand cloth I made him fine and smooth and polished him until the marble was as silken as a woman’s armpit hair and about me there lay chunks of debris and white powder fine as ash—

I think of the many friends I have lost to the grave due to plague or war, the many I have forgotten because of my negligence or overindulgence, my family back in Caprese—my mother and father to whom I send every cent I earn—and Sofia, sweet Sofia, who took to a nunnery in Rome rather than to my adulterous bed—now, in the middle of all these people come to crowd about the Palazzo della Signoria just to see my statue, I am left with these fading images and I am become more wholly at home in the realm of God—I exist as though a spirit until I find myself with pitching chisel in hand and then I am made God’s errand boy again, sent to find the figures hidden in the stone, and with each stroke I earn my place in Heaven where God’s hands will envelop me, hide me for eternity, where only He, the ultimate artist, will be able to divine my self secreted within the stone.

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci

(a.k.a. The Renaissance Man), 53, Creator of Various Charcoal Davids, 1505

I know he knows of my trials, the attempts to put me in chains with claims of sodomy—even though I was acquitted, he looks at me askance as if he sees me as Donatello’s David, effete and limp but a hero nonetheless, because I’ve seen him admire my Annunciation, my Last Supper, my Vitruvian Man, with as much intensity as I have attended his sculpture, stood at its feet night and day and run my hands over its marble until I felt its warm bones beneath and its blood quick in the veins, and any man who could make that perfect male form must also have within him the same love and longing as I—yet no matter how long I sketched his sculpture I could not find its grace.

Would that I were craftsman enough to complete the triumvirate—three Davids of Florence facing south and staring down Rome, the giant—instead I merely sat scribbling these drawings and that is my shame—I cannot meet his measure—oh, that I could give my David the supple, fluid qualities of Donatello’s—whose body is nimble and shows God’s good grace—and the hard, torqued strength of Michelangelo’s—whose body is perfect, thereby reflecting the perfection of his character—I had such a plan to put mine between the two, the bridge between the thought and victory, the stone just leaving his sling, his body twisting like this smoke about me, the man in action.

Yet I have set each of my charcoal sketches afire though I know paper cannot burn—it must first be altered in substance, changed from solid to gas, so then it may burn—I do not mention these ideas for fear they’d incarcerate me for heresy but I’ve witnessed long enough my studies transforming into ghosts of their former selves, spirits that ignite and vapors that flame—fifty-one studies in all going up in the blackest smoke, twisting and twirling like David in action, phantoms rising out the chimney, and so I burn them all but one, my love letter to Michelangelo.

A Prediction Come to Pass: Gabriel, Comte de Montgomery v. King Henry II

On the Grounds of the Place Royale in Paris, France,

June 30, 1559

Gabriel, Comte de Montgomery, 29,

French Nobleman & Captain in Henry II’s Scots Guards

In my heart I have already converted—what use have I of pope or any other intercession—I love the king, I swear I do, but I do not love his ban—I bite my tongue and hear my heart pound under this armor—sweat runs in sheets down my back and my hair mats against my skull, my mouth dry and my wineskin empty—I ask my squire for the wooden-tipped lance, the kind they used in olden days—the banners of peace are blowing about us and they are in riotous celebration, musicians and dancers, a makeshift abattoir where oxen and lambs are slaughtered—hawkers and draught pourers, jugglers and dove sellers—so it should be, King Henry has restored peace to all of Europe and his daughter will wed King Philip of Spain—the Catholics are smug as ever and raise their glasses, while the Protestants scurry in shadow and fear—I close my visor and mark the holy cross against my chest and the king returns the gesture—I salute him and the audience roars and I heft my s

hield with the golden lion painted ’cross it and my horse runs his hoof through the dirt and I understand what needs be done—the flag is dropped and we charge—I bring the lance down late and, catching the king by his mask, it splinters into a thousand pieces, and so he is undone—

I know this will be my undoing—I will be forced from this land, but I will return like Jesus with my army, prepared to beat this palace to dust and rebuild it within three days’ time.

Henry II, 40,

Duc d’Orleans & King of France

My mare has ridden strong today and sweat froths on her hide and I lean into her neck and whisper, This is your last run, mi amour, and I stroke her mane that some servant has perfumed, the odor of lilacs and roses rises into my face, and I am a small child again in the royal garden tossing a red ball high in the air and catching it and rolling it down the lanes and running after it and catching it up again and darting through that labyrinth of hedges and fleeing from my nurses and guards until they could no longer find me and still I ducked through bushes and ran around great rock piles and fountains and statues of my king father and statues of my queen mother and I laughed to myself as they called my name and I ran into a clearing, a sight I’d never seen, hundreds of rosebushes all blooming reds and yellows and pinks and again I tossed my ball, red as the red roses, higher than ever, and as I watched it rise like a bleeding sun, I stumbled back into one of the bush’s thorny arms and it caught me and bit my skin and burned and would not let me go—and no matter how loud I cried for my nurses and for my guards and for my king and for my queen no one came and I was bloodied and burning, alone—

The Book of Duels

The Book of Duels